Émile Zola, L'Oeuvre (Masterpiece)

Early in his career Zola had written in defense of Manet, and he saw a link between his own naturalistic fiction and the efforts of the early Impressionists to move beyond the classicism of the Academy. But by the mid-1880s he was becoming disenchanted with an art that he believed was abandoning reality. In 1886 he published L'Oeuvre, a novel that cast the new artistic tendencies as signs of madness and decay. The central character of the novel, Claude Lantier, has elements borrowed from the lives and work of Manet and Monet, but it is largely based on Paul Cézanne, who had been a close friend of Zola when they were growing up in Aix-en-Provence.

In L'Oeuvre the novelist Pierre Sandoz, clearly Zola himself, watches as Lantier slowly abandons naturalism and becomes obsessed with art for its own sake. He becomes obsessed with a painting of the Ile de la Cité in Paris in which he insists on adding nude women bathing. As he descends into madness, he endlessly alters the painting, until he finally hangs himself in front of it.

Below are a few passages from the novel in which Zola expresses his dismay at the direction that artists such as Cezanne were taking. They demonstrate how bewildering the changes in art even to those who had applauded early Impressionism

One day Claude, who, so far, had not opened his door to his friends, condescended to admit Sandoz. The latter tumbled upon a study with a deal of dash in it, thrown off without a model, and again admirable in colour. The subject had remained the same--the Port St. Nicolas on the left, the swimming-baths on the right, the Seine and Cite in the background. But Sandoz was amazed at perceiving, instead of the boat

sculled by a waterman, another large skiff taking up the whole centre of the composition--a skiff occupied by three women. One, in a bathing costume, was rowing; another sat over the edge with her legs dangling in the water, her costume partially unfastened, showing her bare shoulder; while the third stood erect and nude at the prow, so bright in tone that she seemed effulgent, like the sun.

'Why, what an idea!' muttered Sandoz. 'What are those women doing there?'

'Why, they are bathing,' Claude quietly answered. 'Don't you see that they have come out of the swimming-baths? It supplies me with a motive for the nude; it's a real find, eh? Does it shock you?'

His old friend, who knew him well by now, dreaded lest he should give him cause for discouragement.

'I? Oh, no! Only I am afraid that the public will again fail to understand. That nude woman in the very midst of Paris--it's improbable.'

Claude looked naively surprised.

'Ah! you think so? Well, so much the worse. What's the odds, as long as the woman is well painted? Besides, I need something like that to get my courage up.'

On the following occasions, Sandoz gently reverted to the strangeness of the composition, pleading, as was his nature, the cause of outraged logic. How could a modern painter who prided himself on painting merely what was real--how could he so bastardise his work as to introduce fanciful things into it? It would have been so easy to choose another subject, in which the nude would have been necessary. But Claude became obstinate, and resorted to lame and violent explanations, for he would not avow his real motive: an idea which had come to him and which he would have been at a loss to express clearly. It was, however, a longing for some secret symbolism. A recrudescence of romanticism made him see an incarnation of Paris in that nude figure; he pictured the city bare and impassioned, resplendent with the beauty of woman.

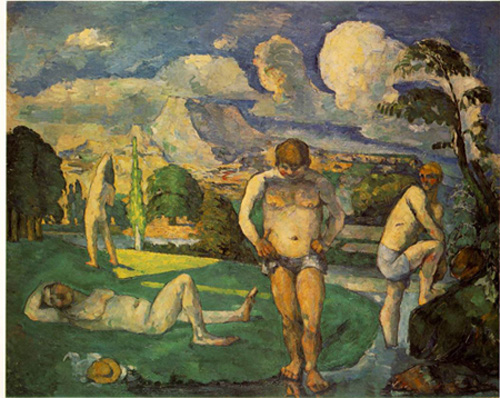

Paul Cézanne, Bathers at Rest (1875-76)

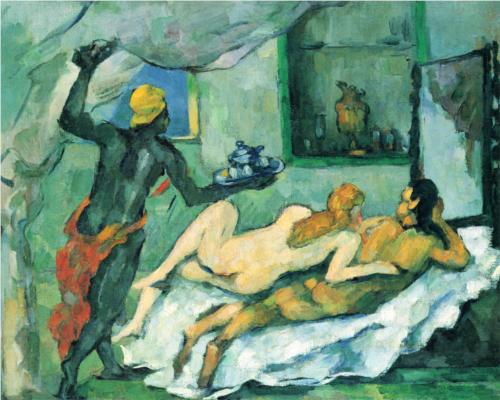

Paul Cezanne, Afternoon in Naples (1875)

Later in the novel Zola describes the kinds of new techniques being developed by artists such as Seurat as symptoms of Claude's madness.

As this unhinging of Claude's faculties increased, he drifted into a sort of superstition, into a devout belief in certain processes and methods. He banished oil from his colours, and spoke of it as of a personal enemy. On the other hand, he held that turpentine produced a solid unpolished surface, and he had some secrets of his own which he hid from everybody; solutions of amber, liquefied copal, and other resinous compounds that made colours dry quickly, and prevented them from cracking. But he experienced some terrible worries, as the absorbent nature of the canvas at once sucked in the little oil contained in the paint. Then the question of brushes had always worried him greatly; he insisted on having them with special handles; and objecting to sable, he used nothing but oven-dried badger hair.

More important, however, than everything else was the question of palette-knives, which, like Courbet, he used for his backgrounds. He had quite a collection of them, some long and flexible, others broad and squat, and one which was triangular like a glazier's, and which had been expressly made for him. It was the real Delacroix knife. Besides, he never made use of the scraper or razor, which he considered beneath an artist's dignity. But, on the other hand, he indulged in all sorts of mysterious practices in applying his colours, concocted recipes and changed them every month, and suddenly fancied that he had bit on the right system of painting, when, after repudiating oil and its flow, he began to lay on successive touches until he arrived at the exact tone he required. One of his fads for a

long while was to paint from right to left; for, without confessing as much, he felt sure that it brought him luck. But the terrible affair which unhinged him once more was an all-invading theory respecting the complementary colours. Gagniere had been the first to speak to him on the subject, being himself equally inclined to technical speculation. After which Claude, impelled by the exuberance of his passion, took to exaggerating the scientific principles whereby, from the three primitive colours, yellow, red, and blue, one derives the three secondary ones, orange, green, and violet, and, further, a whole series of complementary and similar hues, whose composites are obtained mathematically from one another. Thus science entered into painting, there was a method for logical observation already. One only had to take the predominating hue of a picture, and note the complementary or similar colours, to establish experimentally what variations would occur; for instance, red would turn yellowish if it were near blue, and a whole landscape would change in tint by the refractions and the very decomposition of light, according to the clouds passing over it. Claude then accurately came to this conclusion: That objects have no real fixed colour; that they assume various hues according to ambient circumstances; but the misfortune was that when he took to direct observation, with his brain throbbing

with scientific formulas, his prejudiced vision lent too much force to delicate shades, and made him render what was theoretically correct in too vivid a manner: thus his style, once so bright, so full of the palpitation of sunlight, ended in a reversal of everything to which the eye was accustomed, giving, for instance, flesh of a violet tinge under tricoloured skies. Insanity seemed to be at the end of it all.

He would never finish that picture, that was quite certain now. The more desperately he worked at it, the more incoherent did it become; the

colouring had grown heavy and pasty, the drawing was losing shape and showing signs of effort. Even the background and the group of labourers, once so substantial and satisfactory, were getting spoiled; yet he clung to them, he had obstinately determined to finish everything else before repainting the central figure, the nude woman, which remained the dread and the desire of his hours of toil, and which would finish him off whenever he might again try to invest it with life.